Week 9

Unix processes and exceptional control flow

This lecture covers:

- Overall organization of Unix

- The concept of a process.

- Passing output from one process as input to another using pipes.

- Redirecting process input and output.

- Controlling processes associated with the current shell.

- Controlling other processes.

- Exceptional control flow in unix.

- Signals and jumps.

The big picture

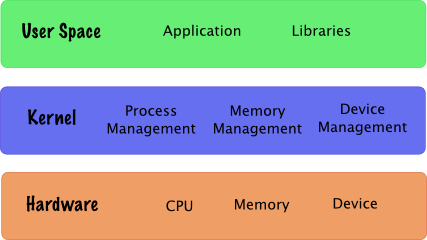

The Partition Between Kernel and User Space

In the UNIX operating system, applications do not have direct access to the computer hardware (say a hard-drive). Applications have to request hardware access from a third-party that mediates all access to computer resources, the Kernel.

As you can see from the above diagram, the Kernel is a central component of most computer operating systems. The kernel's main responsibilities are to:

- Provide an abstraction layer on top of the hardware on which the system operates. In this way, the Kernel acts as a standard interface to the system hardware: for example, when an application reads a file it does not have to be aware of the hard-drive model or physical geometry.

- Be in charge of managing computer resources. Since the machine and its devices are shared between multiple users and programs, access to those resources must be synchronized. The Kernel implements and guarantees a (relatively) fair access to the processor, the memory and the devices. In particular, the Kernel is in charge of process management and prevents a misbehaving process from monopolizing the CPU1.

- Implement multitasking. Each process gets the illusion that it is running uninterrupted on its own processor. In reality, multiple processes compete continuously for system resources: the Kernel keeps switching the active process for each processor behind the scene.

- Enforce isolation between processes. Because the Kernel mediates access to all system resources it can guarantee that one process cannot corrupt the execution environment of another process. For instance, each process has its own virtual memory and cannot access the memory that the Kernel allocated to another process2.

The Kernel can also be seen as one abstraction layer part of the traditional computer architecture design in which each layer relies solely on the functions of the layers beneath itself. Its mission is to protect users and applications from each others and to provide a simple metaphor that shields applications from most of the system complexity.

Now that we understand better what constitutes the Kernel Space, you might wonder what User Space is. Well it is actually quite simple: User Space is everything else! More exactly, all the software running on a UNIX system except the Kernel (and its device drivers) is running in User Space.

What is a Unix process?

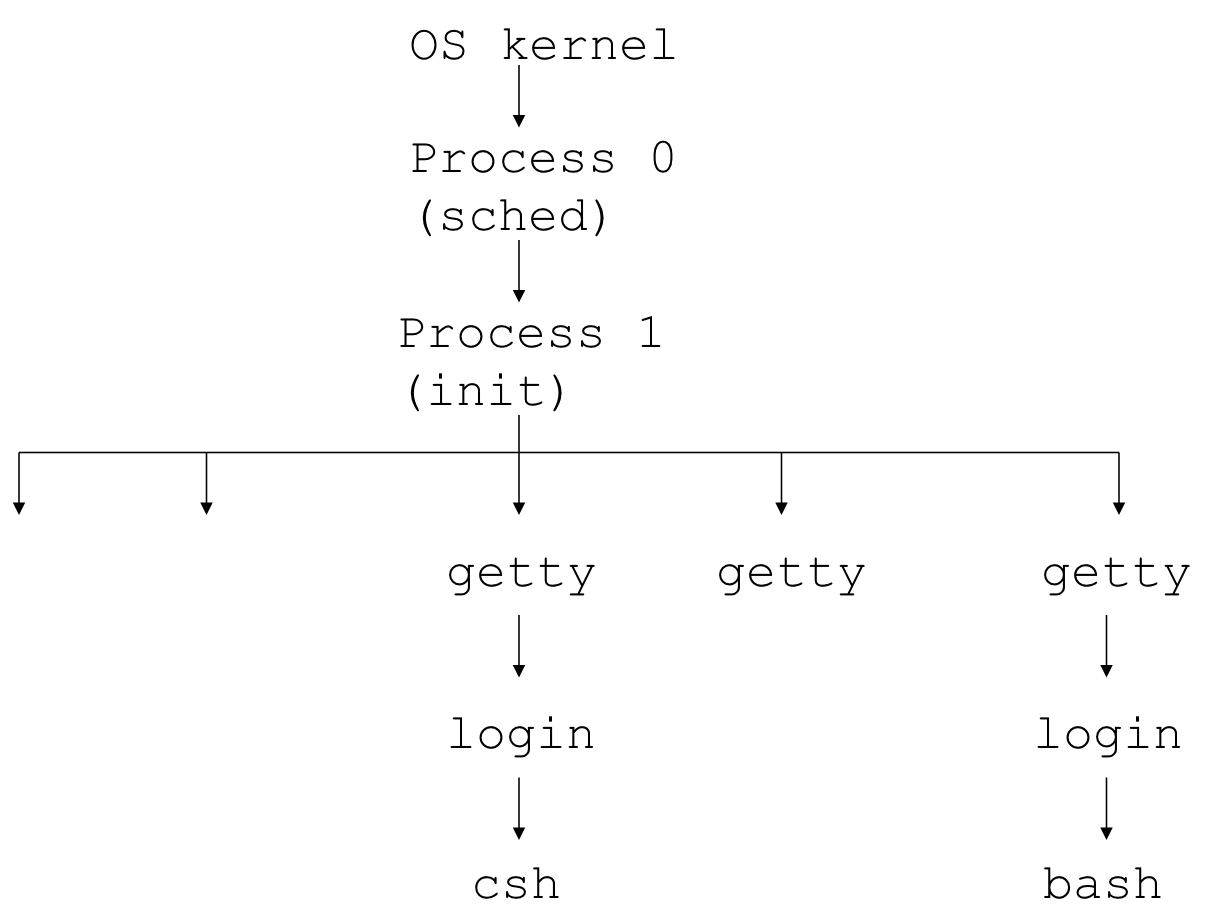

A process is a program in execution. The Unix shell is a process. Every time you invoke a system utility or an application program from a shell, one or more child processes are created by the shell in response to your command. All UNIX processes are identified by a unique process identifier or PID.

An important process that is always present is the init process. This is the first process to be created when a UNIX system starts up and usually has a PID of 1. All other processes are said to be descendants of init.

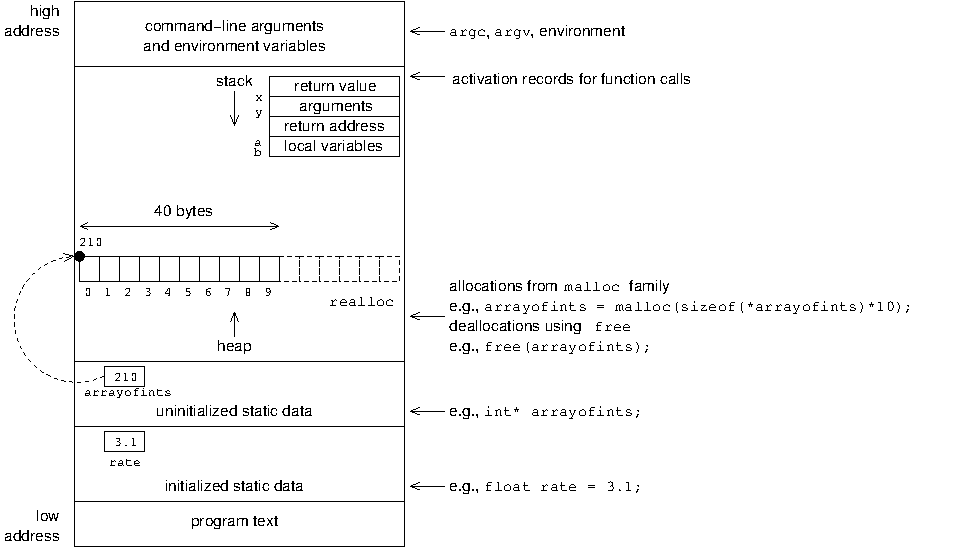

What makes up a Unix process?

- program code

- machine registers

- global data

- stack

- open files (file descriptors)

- an environment (environment variables; credentials for security)

Important: processes are sequential.

Some of the Unix process context information:

- Process ID (pid): unique integer

- Parent process ID (ppid)

- Real user ID: ID of the user or process which started this process

- Effective user ID: ID of user who created the process's program

- Current directory

- File descriptor table

- Environment:

VAR=VALUEpairs - Pointer to program code

- Pointer to data: memory for global variables

- Pointer to stack: memory for local variables

- Pointer to heap: dynamically allocatable memory

- Execution priority

- Signal information

Logical program layout

Pipes

The pipe ('|') operator is used to create concurrently executing processes that pass data directly to one another. It is useful for combining system utilities to perform more complex functions. For example:

$ cat hello.txt | sort | uniq

creates three processes (corresponding to cat, sort and uniq) which execute concurrently. As they execute, the output of the who process is passed on to the sort process which is in turn passed on to the uniq process. uniq displays its output on the screen (a sorted list of users with duplicate lines removed). Similarly:

$ cat hello.txt | grep "dog" | grep -v "cat"

finds all lines in hello.txt that contain the string "dog" but do not contain the string "cat".

Redirecting input and output

The output from programs is usually written to the screen, while their input usually comes from the keyboard (if no file arguments are given). In technical terms, we say that processes usually write to standard output (the screen) and take their input from standard input (the keyboard). There is in fact another output channel called standard error, where processes write their error messages; by default error messages are also sent to the screen. To redirect standard output to a file instead of the screen, we use the > operator:

$ echo hello

hello

$ echo hello > output

$ cat output

hello

In this case, the contents of the file output will be destroyed if the file already exists. If instead we want to append the output of the echo command to the file, we can use the >> operator:

$ echo bye >> output

$ cat output

hello

bye

To capture standard error, prefix the > operator with a 2 (in UNIX the file numbers 0, 1 and 2 are assigned to standard input, standard output and standard error respectively), e.g.:

$ cat nonexistent 2>errors

$ cat errors

cat: nonexistent: No such file or directory

$

You can redirect standard error and standard output to two different files:

$ find . -print 1>errors 2>files

or to the same file:

$ find . -print 1>output 2>output

or

$ find . -print >& output

Standard input can also be redirected using the < operator, so that input is read from a file instead of the keyboard:

$ cat < output

hello

bye

You can combine input redirection with output redirection, but be careful not to use the same filename in both places. For example:

$ cat < output > output

will destroy the contents of the file output. This is because the first thing the shell does when it sees the > operator is to create an empty file ready for the output.

One last point to note is that we can pass standard output to system utilities that require filenames as "-":

$ cat package.tar.gz | gzip -d | tar tvf -

Here the output of the gzip -d command is used as the input file to the tar command.

Combining pipes and output redirection

As you have noticed, sometimes you wish to see only part of an output of a command (e.g., when you have a lot of syntax errors when compiling templated C++ code and only want to see the first one). Here is a command that redirects standard error to standard output, then pipes the result through the head command (which only displays the first few lines):

$ make 2>&1 | head

To see a certain number of lines, e.g., 20:

$ make 2>&1 | head -n 20

Controlling processes associated with the current shell

Most shells provide sophisticated job control facilities that let you control many running jobs (i.e. processes) at the same time. This is useful if, for example, you are editing a text file and want ot interrupt your editing to do something else. With job control, you can suspend the editor, go back to the shell prompt, and start work on something else. When you are finished, you can switch back to the editor and continue as if you hadn't left. Jobs can either be in the foreground or the background. There can be only one job in the foreground at any time. The foreground job has control of the shell with which you interact - it receives input from the keyboard and sends output to the screen. Jobs in the background do not receive input from the terminal, generally running along quietly without the need for interaction (and drawing it to your attention if they do).

The foreground job may be suspended, i.e. temporarily stopped, by pressing the Ctrl-Z key. A suspended job can be made to continue running in the foreground or background as needed by typing "fg" or "bg" respectively. Note that suspending a job is very different from interrupting a job (by pressing the interrupt key, usually Ctrl-C); interrupted jobs are killed off permanently and cannot be resumed.

Background jobs can also be run directly from the command line, by appending a '&' character to the command line. For example:

$ find / -print 1>output 2>errors &

[1] 27501

$

Here the [1] returned by the shell represents the job number of the background process, and the 27501 is the PID of the process. To see a list of all the jobs associated with the current shell, type jobs:

$ jobs

[1]+ Running find / -print 1>output 2>errors &

$

Note that if you have more than one job you can refer to the job as %n where n is the job number. So for example fg %3 resumes job number 3 in the foreground.

To find out the process ID's of the underlying processes associated with the shell and its jobs, use ps (process show):

$ ps

PID TTY TIME CMD

17717 pts/10 00:00:00 bash

27501 pts/10 00:00:01 find

27502 pts/10 00:00:00 ps

So here the PID of the shell (bash) is 17717, the PID of find is 27501 and the PID of ps is 27502.

To terminate a process or job abruptly, use the kill command. kill allows jobs to referred to in two ways - by their PID or by their job number. So

$ kill %1

or

$ kill 27501

would terminate the find process. Actually kill only sends the process a signal requesting it shutdown and exit gracefully (the SIGTERM signal), so this may not always work. To force a process to terminate abruptly (and with a higher probability of sucess), use a -9 option (the SIGKILL signal):

$ kill -9 27501

kill can be used to send many other types of signals to running processes. For example a -19 option (SIGSTOP) will suspend a running process. To see a list of such signals, run kill -l.

Controlling other processes

You can also use ps to show all processes running on the machine (not just the processes in your current shell):

$ ps -fae(or ps -aux on BSD machines)

and ps -aeH displays a full process hierarchy (including the init process).

Many UNIX versions have a system utility called top that provides an interactive way to monitor system activity. Detailed statistics about currently running processes are displayed and constantly refreshed. Processes are displayed in order of CPU utilization. Useful keys in top are:

s - set update frequency k - kill process (by PID)

u - display processes of one user q - quit

On some systems, the utility w is a non-interactive substitute for top.

One other useful process control utility that can be found on most UNIX systems is the pkill command. You can use pkill to kill processes by name instead of PID or job number. So another way to kill off our background find process (along with any another find processes we are running) would be:

$ pkill find

[1]+ Terminated find / -print 1>output 2>errors

$

Note that, for obvious security reasons, you can only kill processes that belong to you (unless you are the superuser).

Another kill-by-name command is killall. There are some differences between the available options for pkill and killall (e.g., killall has a flag to match by process age, pkill has a flag to only kill processes on a given tty). Neither is better, most of the time it doesn't matter which one you use.

Running processes as another user

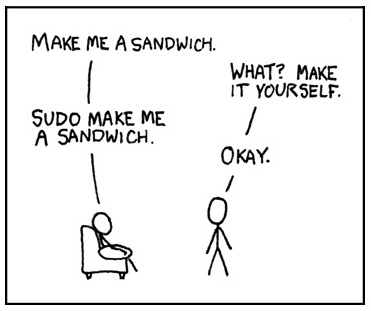

Sudo stands for either "substitute user do" or "super user do" (depending upon how you want to look at it). What sudo does is incredibly important and crucial to many Linux distributions. Effectively, sudo allows a user to run a program as another user (most often the root user). When using sudo, users authenticate using their own password (unlike su, which requires the root password).

Most frequently you would use sudo to install or remove packages:

$ sudo dpkg -i zip $ sudo dpkg -r zip

Exceptional control flow and Unix processes

Reference: CSAPP2e Chapter 8

Slides: PDF, 4-up PDF

Code: Lecture code repo, week9

Signals and Jumps

Reference: CSAPP2e Chapter 8

Slides: PDF, 4-up PDF

Code: Lecture code repo, week9

Distractions