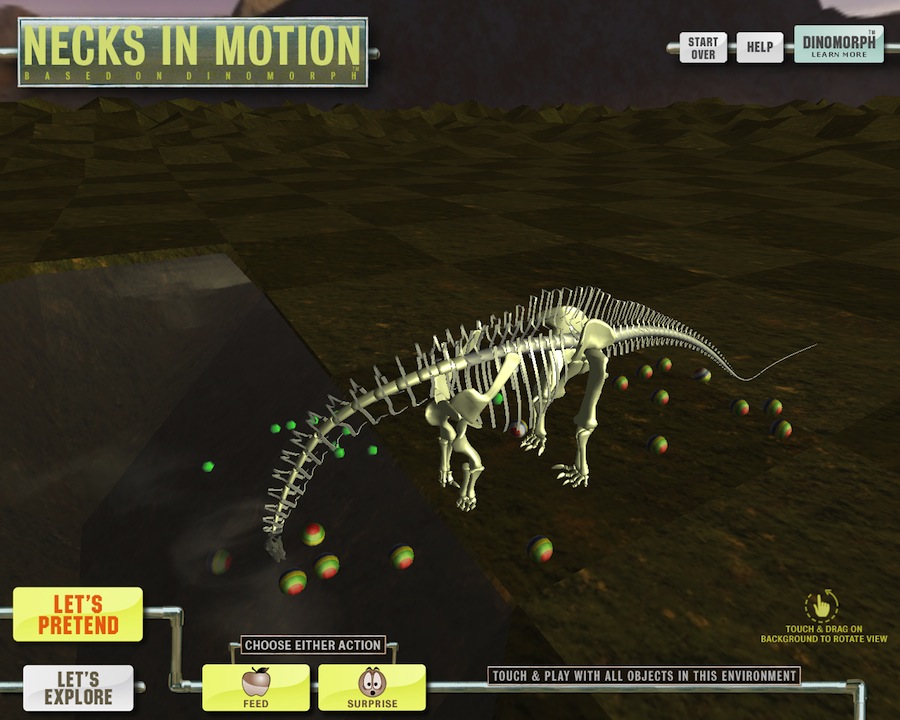

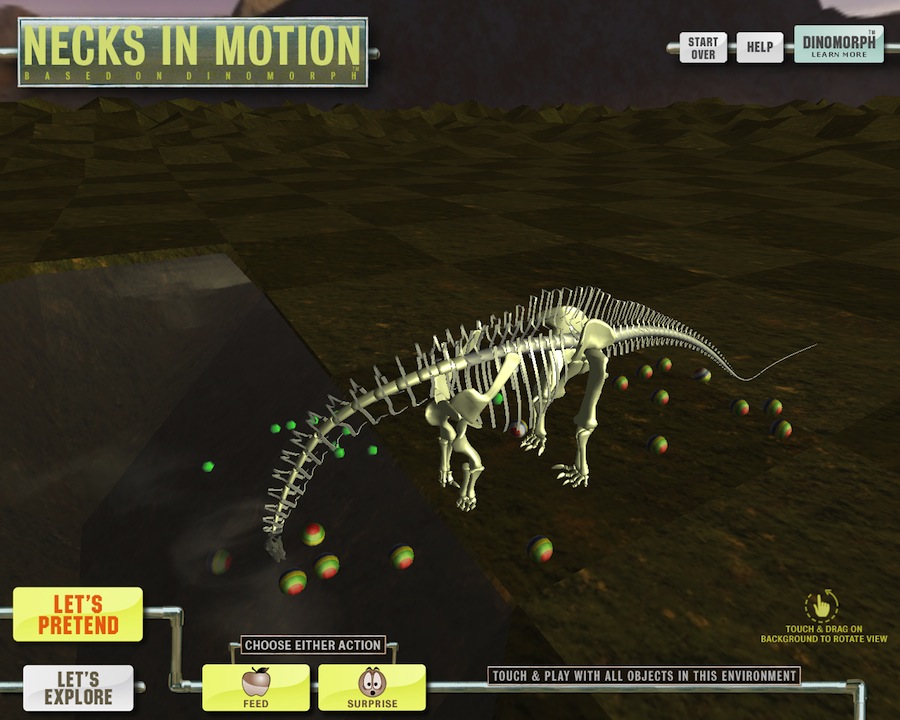

One of two touch screens running the "Necks in Motion" interactive kiosk program by Kaibridge, Inc. Photo courtesy Rick Edwards, AMNH

| In 2003, Dr. Mark Norell, Chair and Curator of the Division of Paleontology, proposed a traveling exhibition that in part focusses upon John Hutchison's digital study of Tyrannosaurus rex and our DinoMorph™, each with computer graphic interactives, physical sculptures and video interviews. The DinoMorph™ engine was used to create our sauropod neck mobility demonstration. |

|

|

Touch screen interactive showing two diplodocid sauropods (the robust Apatosaurus and the more gracile, longer necked, but surprisingly less flexible Diplodocus) and a modern giraffe for comparison. The range of motion can be explored using the controller in the lower right, plus zoom and rotation of the viewpoint. The sauropods demonstrate the potential for aquatic feeding with simulated water.

|

|

|

After clicking "Let's Pretend", museum visitors can interact

with Apatosaurus, feeding it (apples drop and are picked up and swallowed) and by moving beach balls

around for it to play with. The dinosaur reacts to touch and is a bit ticklish and will try to maintain its balance

if you try to pull or push it around.

|

|

|

One of two touch screens running the "Necks in Motion" interactive kiosk program by Kaibridge, Inc. Photo courtesy Rick Edwards, AMNH |

|

The exhibitions staff at the AMNH were great to work with. They us let us create a spontaneous interactive application entirely built upon the DinoMorph™ engine, instead of a conventional "canned" kiosk-style demo. Two touch-screen displays running the "Necks in Motion" software illustrate the range of motion of the neck of two huge sauropods and, for the first time, permitting one to compare these sauropod feeding envelopes with that of a modern giraffe. The AMNH artists designed the graphical user interface and we provided the engine behind the interface. The interactives also give a sense for where we are going with DinoMorph™ when visitors shift to the "let's pretend" mode: Apatosaurus comes alive within a physical environment of apples that fall into the water (and after bobbing for apples, a couple of apples are swallowed and travel down the long neck to the gut where they literally shake the ribs as they bounce about). The sauropod can also play with beach balls that fall from the sky. We also give the animal reactivity to the visitor's touch (the interactives are presented, after all, on a touch screen). We introduced a far more mammalian personality than would be expected of a sauropod, including a decidely ticklish (indeed skitterish) body sense which, for the persistent visitor, can cause it to slip into the pond. And thanks also to so many others associated with the careful planning and execution of the exhibition, including (left to right) Dee Dixon, Mike Cosaboom, Harry Borelli, and Geralyn Abinader, and Tim Nissen (right image) holding a mockup of the Apatosaurus sculpture at an early stage of floorplan design. |

|

|

Why the Art Deco Dino?For much the same reason that Art Deco is so effective in visually conveying (both 3D and 2D) shape by means of simplified (and often stylized) contours, the rendition of bone morphology in DinoMorph™ often emphasizes the rendering of those morphological features that matter most for addressing a given research problem. An example is the DinoMorph™ modeling of two rather different designs of sauropod neck (robust Apatosaurus versus gracile Diplodocus): articular facets of the zygapophyses were modeled in detail while the remainder of the vertebrae were represented only schematically, permitting us to focus on zygapophysis shape in particular. We found that the curved zygapophyses associated with the gracile design could have provided stability when the necks were flexed laterally to their limit. While first noticed when manipulating a very simplified model, this osteological bracing principle is also present in the giraffe neck (as observed in a DinoMorph™ model created to demonstrate the range of motion of the giraffe neck, for comparison with that of the sauropods). |

| There is no unique visual representation of bone morphology; the more detailed the model, the more one necessarily shifts from a generic representation to presenting the details of a particular specimen, the idiosyncrasies of which may obscure the important designs features of its taxon. When provided actual scan data from a particular specimen, the option is available to replace the schematic and simplified bone bone with "the real thing". That is but one end of a continuum from abstract to specific. |

|

|

| I find it quite fitting that this metallic sculpture appears in a city so rich in Art Deco. The simplification of geometric form to accentuate the important contours and shapes is probably something of both artistic and scientific appeal, given a desire to reduce form to its essentials. Photo courtesy Rick Edwards, AMNH. |

|

|

|

The 60 foot sub-adult Apatosaurus was fabricated by Research Casting International (Toronto) based on digital 3D data that was exported directly from DinoMorph™. Oh, and why not a full adult? A matter of ceiling height in some of the venues to which it travels. |

Copyright © 2011 Kent A. Stevens, University of Oregon