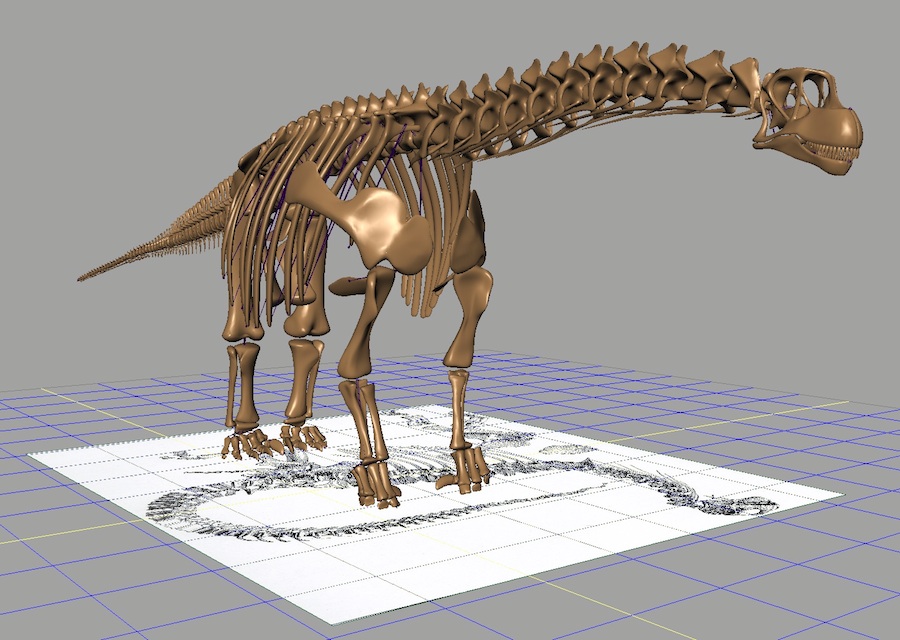

then Camarasaurus was likely to have had this sort of overall bauplan:

Clearly Camarasaurus was a medium to high browser (depending on the size of the individual), but it naturally achieved head height by simply its shoulder height. Add to this the ability to dorsiflex considerably, and Camarasaurus was likely capable of browsing from ground height to about 6 m (or more, for very large individuals).

There has been, however, a tradition of showing Camarasaurus as swan-necked. I've examined a large number of specimens, some of the best preserved are not generally available to the public, and present in the following documentation of what the neck bones really look like. When rearticulated they fit together just as I have seen for other sauropods: as straight at the shoulder. In situ they were frequently found with a death pose, dorsiflex, particularly at the base of the neck. But Camarasaurus and Brachiosaurus (and a few others, as depicted by a few artists) are given an upturn at the base of the neck.

There are seemingly only three possible explanations that could account for the elevation one finds in such enthusiastic renditions. First, note that two of the following explanations do not question the osteological evidence that the individual cervical vertebrae are not keystoned or wedge-shaped (such as those at the base of the giraffe, which causes the giraffe's neck to ascend in the neutral, undeflected state). The third explanation would require that one ignore the great bulk of osteological evidence against giraffe-like specializations for neck elevation.

How to make a camarasaurid neck look giraffe-like (three alternatives):

1. Propose habitual muscular exertion. The first alternative accepts that camarasaurids had necks that were indeed straight when undeflected, just as the bones suggest in ONP, but that the animals, in life, habitually dorsiflexed the neck. This is the case with some grazers (e.g., rabbit, ostrich) when not actively eating at ground level, for they would otherwise be subject to surprise predation. They ventriflex to reach the ground when eating, and habitually dorsiflex (raising the head held above ONP) when resting and alert. But modern large herbivores (e.g., giraffe, horse) rest in approximately ONP when vigilant. Their necks naturally provide the head height in the undeflected state to provide a high vantage point for surveillance. Which model applies to the sauropods: the bunny or the wildebeest?

2. Propose thick wedges of cartilage between centra. In the second alternative, again the bones tell a straight story, but an upturn is nonetheless added by wedge-like cartilaginous disks between the opisthocoelous (ball and socket joints) central articulations. Briefly, this is completely at odds with every articulated sauropod cervical vertebral column found in situ, all of which are very tightly fitting as they are in all extant taxa that have this form of articulation (see below).

3. Propose that the vertebrae are actually wedged. One occasionally hears rumors of keystone-shaped Camarasaurid cervicals, which if they were to exist, would indeed create giraffomorphic sauropods. Of course, that morphology would be at odds with a great many individual sauropod cervicodorsal vertebrae that are definitely not keystone-shaped (see photographs below). Adjusting to the idea that Camarasaurus wasn't a Juraffe (Jurassic giraffe) after all.

Mike Parrish and I offer an alternative, but it might takes some attitude adjustment. First, one needs look at Camarasaurus (and other sauropods) with a mind cleared of gee-it-must-be-a-giraffe-because-that's-how-it-is-always-drawn expectations. Just look at the actual osteology and you'll see that the cervical vertebrae at the base of the neck, and the anterior dorsal vertebrae in the region of the shoulders are essentially spool-shaped (as opposed to wedge-shaped), much like we have found in every other sauropod we've examined. It is important to go back to the original material, not the silhouette drawings of skeletal reconstructions that one finds in various dinosaur books where, ahem, a certain degree of artistic license has sometimes been used to make the vertebrae appear wedge-shaped, thereby inducing the familiar giraffe-like elevation. Next, put the together into a series. All extant and extinct vertebrates with opisthocoelous central articulation fit together very tightly (within mm in giraffe, rhino, horse, etc.) and this provides a very strong constraint on how the vertebrae fit together to form a neck. The neck is decidedly straight in the critical region where it emerges from the (approximately horizontal) dorsal vertebral column. The fact that it then heads south (droops) cranially just makes the story all the more interesting. Camarasaurus was simply not giraffe-like, despite the charming appearance in popular artwork. It would seem preferable, in the long run, to align one's aesthetics with the osteology, and consider the implications of a massive mid-height browser with a neck design that placed the head at, or below, the height of the shoulders. Recent museum mounts of Camarasaurus, such as that at the Gunma Museum of Natural History, the University of Kansas Natural History Museum specimen "Annabelle", and the specimen at the Wyoming Dinosaur Center, are adopting a straight-off-the-shoulders neck postures, very much in keeping with the osteological evidence. We would be very interested to see evidence of any sauropod cervicodorsal vertebrae that actually have a wedge or keystone shape. We simply haven't seen any. The following shows photographs we and associates have taken of original fossil material.